April 5 – June 1, 2024

Curated by Ebony L. Haynes

The gallery was very buzzy when I went, pretty crowded with a wide age range of people chatting. Jafa is known for his films—his revision of Taxi Driver is showing concurrently at Gladstone—but the works in his show at David Zwirner’s 52 Walker location are almost all still.

It’s mentioned in the press release that he responds to Cady Noland’s tabloid cut out pieces through his own cutouts. A photograph of Noland even appears in the big group, Large Array II (2024), which pulls out and props up a wider range of cultural references than Noland’s originals. We see the world increasingly through images. What do our brains do with them and why do they stick?

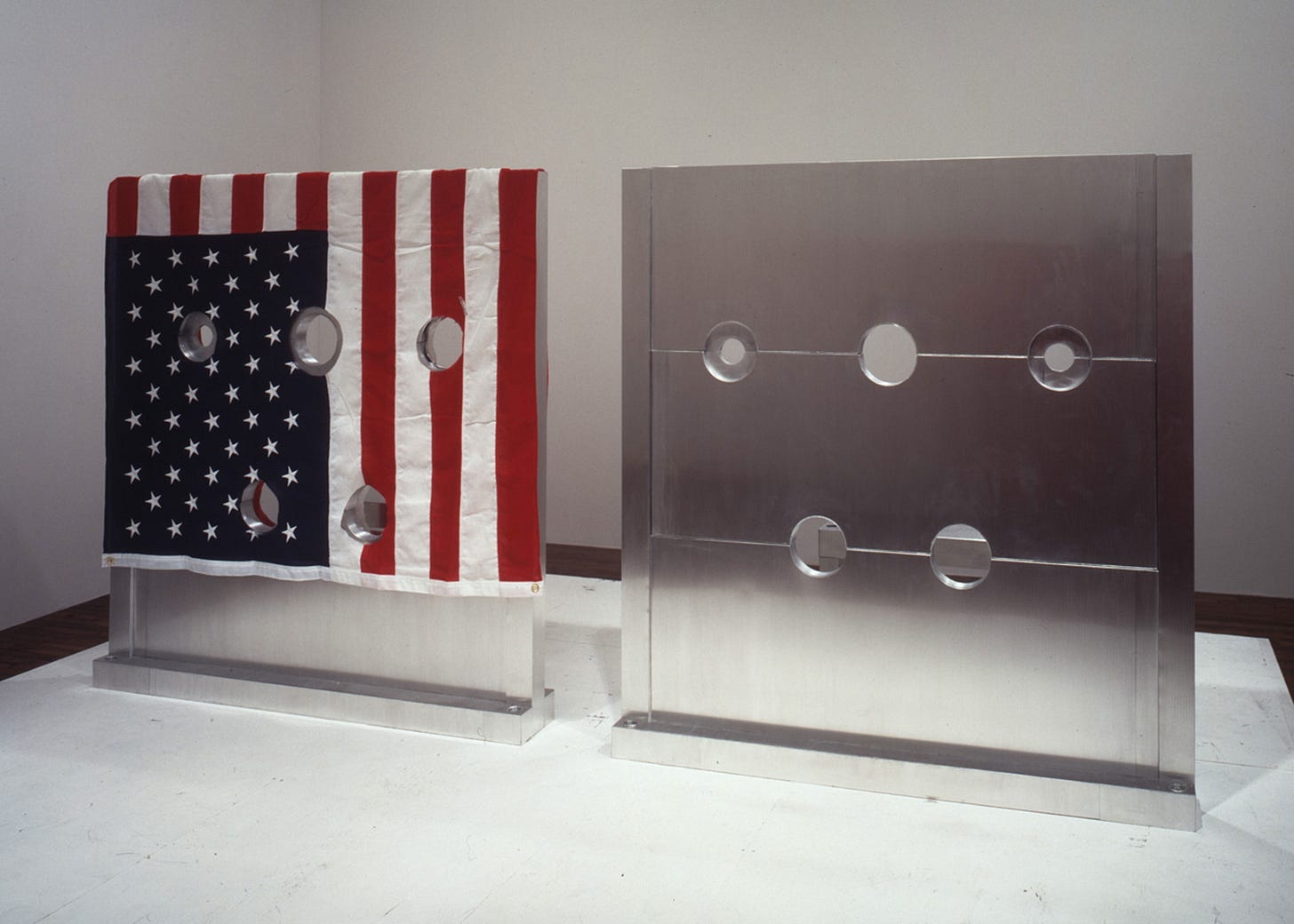

Noland’s fingerprints are all over the rest of the exhibition as well, as seen in the preoccupation with holes and negative space, connecting to Nolands xerox cutouts and her stockade pieces. There’s also the thread of engagement with seemingly found objects. Sculpture made out of materials one would find on the street like traffic bollards, or the sensitively composed wall works made from various lengths of rubber tubes (see Boundary 3). In Jafa and in Noland there seems to be an interest in reframing objects that denote barriers, emphasizing separation, division.

The sleek rail sculptures, hung at head height also echo Noland’s stark metal forms, their sense of scale in tune with human proportions. For Jafa though, they recall the history of film. The entire photo room, Picture Unit (Structures) II, a large room made of black mirrored acrylic and wood, effectively employs the viewer as a camera and encourages us to create our own montage. The enclosed room is centered in the gallery and reflective around the outside. On the inside it mashes together photographs drawn from Jafa’s vast bank of images, blown up to occupy the full size of the walls. The images are rendered in varying levels of graininess, often thematically and visually often in stark and abrupt contrast with each other. In one turn we see Jafa appropriating the arch appropriator Richard Prince, around another turn we face a black light photo of Magic City. The fact that the pictures are arranged in a snaking zig zag means you can only see some of what’s in front of you as you move through the construction. The placement of the black rails emphasizes the role of the viewer in putting together the images, you walking through it effectively becomes a dolly shot, with the viewer’s movement allowing for the combination and juxtaposition of static images in time, like a slow video montage.

The black rails (not pictured my fault I should have taken more pics of the interior didn’t realize they aren’t online), with their sleek polish, decontextualized by being hung on the wall also take on a sort of fetishistic quality. Tools. In this way they function similarly to the rubber and metal pipe relief wall works, like Boundary 3, in this exhibition. I think that’s Jafa’s intention anyway. I’m not sure if the picture unit is entirely successful in achieving this montage effect and at points the box construction felt overly theatrical while also lacking finish—there are visible seams in the vinyl photos inside and the faux wood paneling and led lighting inside felt cheap to me. But I tend to automatically bristle at works that depend too much on a viewer’s experience anyway. Ultimately, it’s cool to see a filmmaker translate something like motion and time into a fine art gallery context.

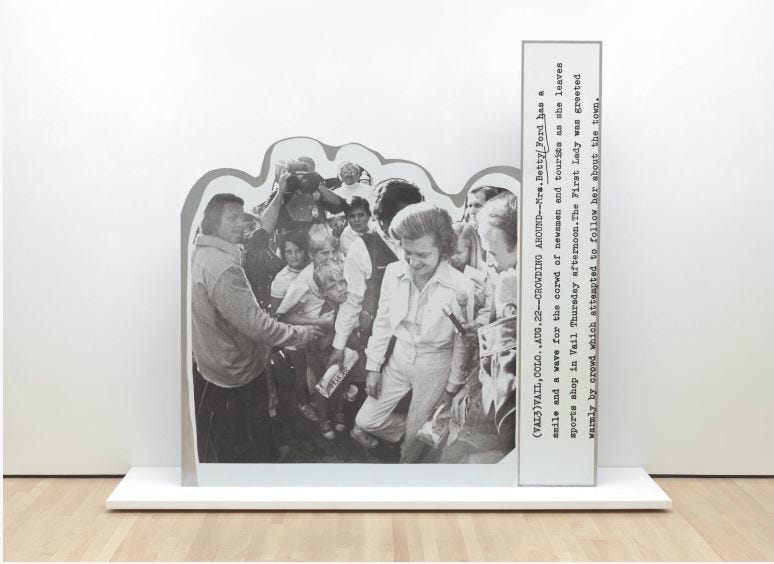

Some of the prints like Garvey /Hendrix (rockstars, celebrity and doom figure heavily in the exhibition) directly recall Cady Noland’s cutouts, with the sources in tabloid reproductions, pop cultural emphasis, and most explicitly in their sideways captions.

American identity as discovered through repetition and seriality are major themes in Cady Noland’s work, and it seems like Jafa is trying to pick those up, reference them, and suffuse them with a wider and more diverse range of sources. He is trying to bring Blackness in to this consideration of American identity through consumer goods, and with a fascinating opacity. On the whole I find this effective and successful. Jafa’s white plastic flag doesn’t seem derivative of Noland’s flag pieces, they seem more like another permutation of the threads she was developing. Not that Cady Noland has a monopoly on flags in postwar art, but since she’s named in the press release I think it’s relevant that she has done a lot of work with the American flag.

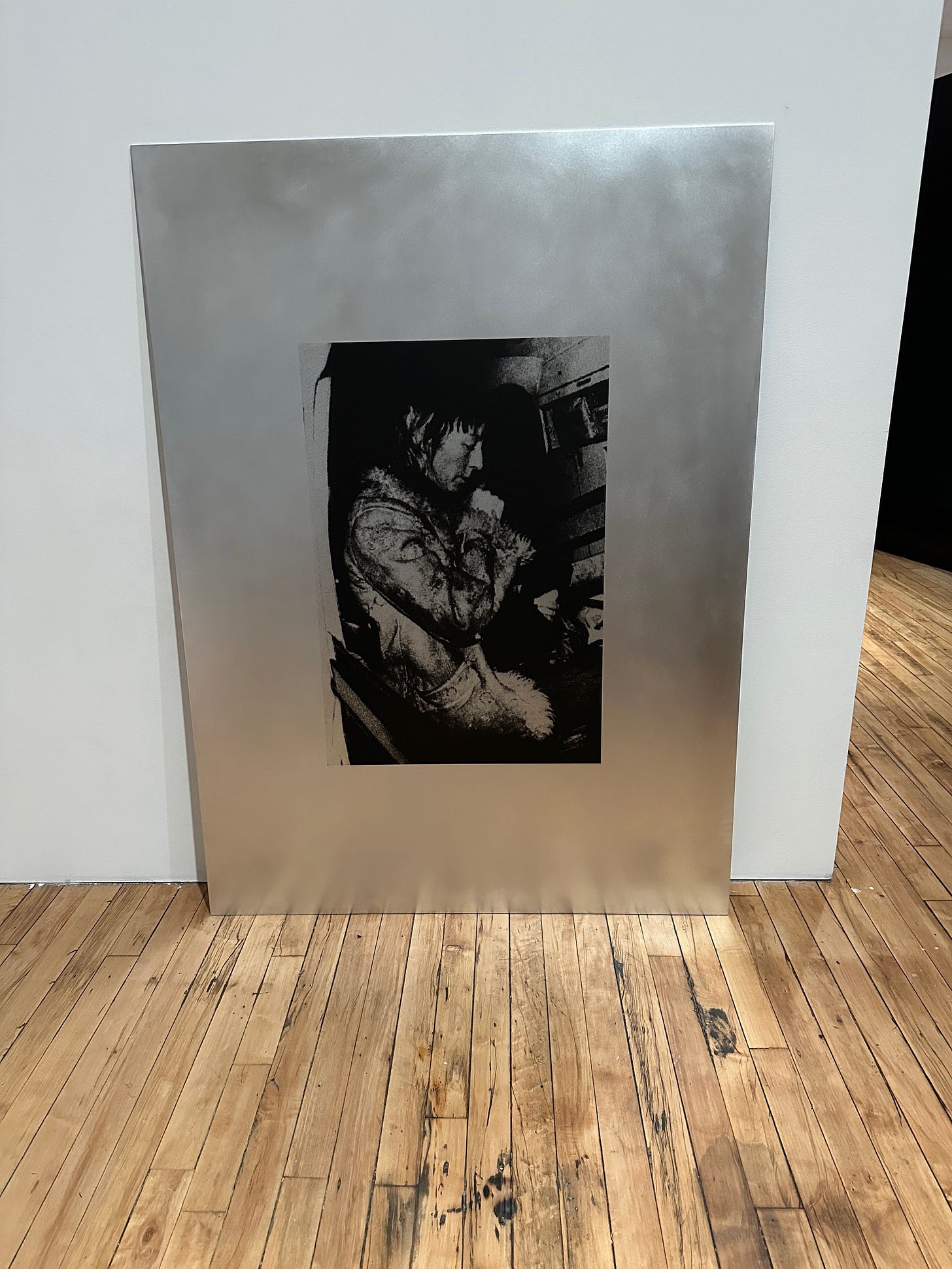

Particularly, I find it interesting how most of Jafa’s overt references to Noland are to a very specific period in her career—the pivotal 1994 exhibition at Paula Cooper gallery. Just by comparing the installation shots, the way pieces are propped against the wall, the news images silkscreened on steel sheets, and especially the cutouts and the holes cut out into the cut outs, it seems clear to me that many of the pieces in the show are responding to this specific exhibition. Occasionally, like the silkscreened steel plates, and the depiction of the Manson family, I do think it dips into being a little too derivative of the source material. When Jafa takes it in his own direction though, the results are remarkable.

Personally, my favorite, and I think the most successful part of the show is what also seemed to me like the centerpiece—the field of cutouts staged behind his large plastic flag piece. Though these cutouts, which appear flimsy, flat, and cardboardy (actually made of dibond), are layered in a shallow space around each other. Sid Vicious, Miles Davis, Adrian Piper, Michel Foucault, a portrait of Jafa himself, among dozens of other references stand among each other like a convening of promotional movie theater installations. I learned from Danielle Jackson’s excellent review in Cultured Mag, which identifies many of the image sources, that one group figures in the background are “investigators examining the car of the murdered civil rights workers James Chaney, Michael Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman.” Throughout the show, relatively neutral images are indiscriminately placed among deeply ominous ones, making it more unsettling to unpack the connections between them. There’s little transition in the jump from comic books to corpses. The dibond pieces are cut out with holes that show through to glimpses of other cut outs, the relationships between what and who he decides to show isn’t always obvious, and some figures have rectangular backgrounds, while others are cut out on the contours of the silhouette of the figure depict.

This piece is, I think, the best example of what sets Jafa apart and above other artists working in post-pictures-generation art (not sure if that’s a thing), or art about the proliferation and repetition of images. That is, a massive vocabulary of pictures collected over decades from every imaginable source coupled with a willingness to combine those contrasting images in ways that breach history, race, and culture, while remaining open ended enough that it doesn’t feel like he’s merely trying to teach you a lesson. At its best, Jafa’s work feels like it digs up something unnamable, if just for a moment.